Review: Residue + Response | 5th Tamworth Textile Triennial

You know I am a huge textiles fan. This review won't come as a surprise at all but I did find something unexpected on my second visit.

As a lover of dressing up, my eye was immediately drawn to Kyra Mancktelow’s two large coat imprints. In the corner of the second room of the exhibition, these two gilt-framed pieces of men’s attire are like many works in the Residue + Response, the 5th Tamworth Textile Triennial, unassuming at first, but richly layered the more time you spend looking at them.

One is a pinkish red coat with military trim and the other an ultramarine blue with buttons and brocade. Composed through an ink impression on beautiful Hahnmuhle paper, the composition is simple. The addition of two Indigenous weapons enhances the tension created by the X-ray quality of the ink. From the series Gubba Up, they constitute an Indigenous interpretation of colonial-era clothing, more specifically the ‘phrase used by First Nations peoples to describe the need to change your way of life to suit your environment’.

First Nations people used the practice of ‘whitening up’ to enter previously inaccessible spaces. Exemption policies, where documentation allowed a person or family to access areas of town usually restricted to whites only, could be seen as an example of this. Being exempt from one’s ‘Aboriginal’ identity, though, came at a cost. At the same time, in the face of assimilation policies and prohibitions to practice their culture, colonised peoples experienced a restricted space in which to talk up.

These were some of the ideas conjured by Mancktelow’s work as I stood in the Mildura Arts Centre recently. The exhibition is touring nationally, and I was thrilled to be able to see this important body of work as it makes its way around the country.

While these two coats are ghostly evocations of the clothing worn by Indigenous people, they are right at home in an exhibition of textiles. They conjure the tactile memories, the feel of the garment. Made from ink and paper (using the technique of frottage) and displayed behind glass with gold frame, Red Coat – Blak Skin and Blue Jacket – Blak Skin from the Gubba Up series, are beyond our touch in the same way as the wearers are for Mancktelow.

Mancktelow, a Quandamooka artist with links to the Mardigan peoples, skillfully draws us into a world of loss, the costs of colonisation. These coats are examples of garments worn by men like Bungaree, who became famous through his relationship with colonists in Sydney and subsequently in oil paintings. His garments are gone, but what remains are described by the artist as ghost artefacts, mere impressions of the man who wore the jacket while subject to ridicule, revulsion or pity.

What grabs me in a work like this is that tension between remembering a painful history and recovering the narrative of the individual Indigenous man or woman whose life played out in spite of, and often in defiance of, the colonial practices designed to erase it.

Mancktelow doesn’t include figures in this series but a sense of identity and corporeality isn’t far away.

In his portrait by Augustus Earle (1826) Bungaree stands confidently, gubba’d up in western attire, holding aloft a copped hat, almost in greeting. The pose is open and not self-important; he smiles. He wears discarded uniforms given to him by the NSW governor and other soldiers. His jacket features gold frogging. The ridicule hits you when you read that Earle has deliberately depicted Bungaree welcoming colonists. Apparently, Bungaree was totally fine with the invasion.

We must examine the lives of men like Bungaree to unpick the narratives his life has been clad in. I think this is why Mancktelow does not include people in this series. Their absence forced me to look for a portrait of an Aboriginal man in European military coat. I knew enough existed to make this a trope, and a quick search brought me to the National Gallery of Australia and Bungaree’s portrait. Many unnamed Aboriginal men and women are instead represented through these clothes sans wearer, reminding me of the intimacy of textiles against skin and the people whose names and deeds weren’t recorded in official accounts.

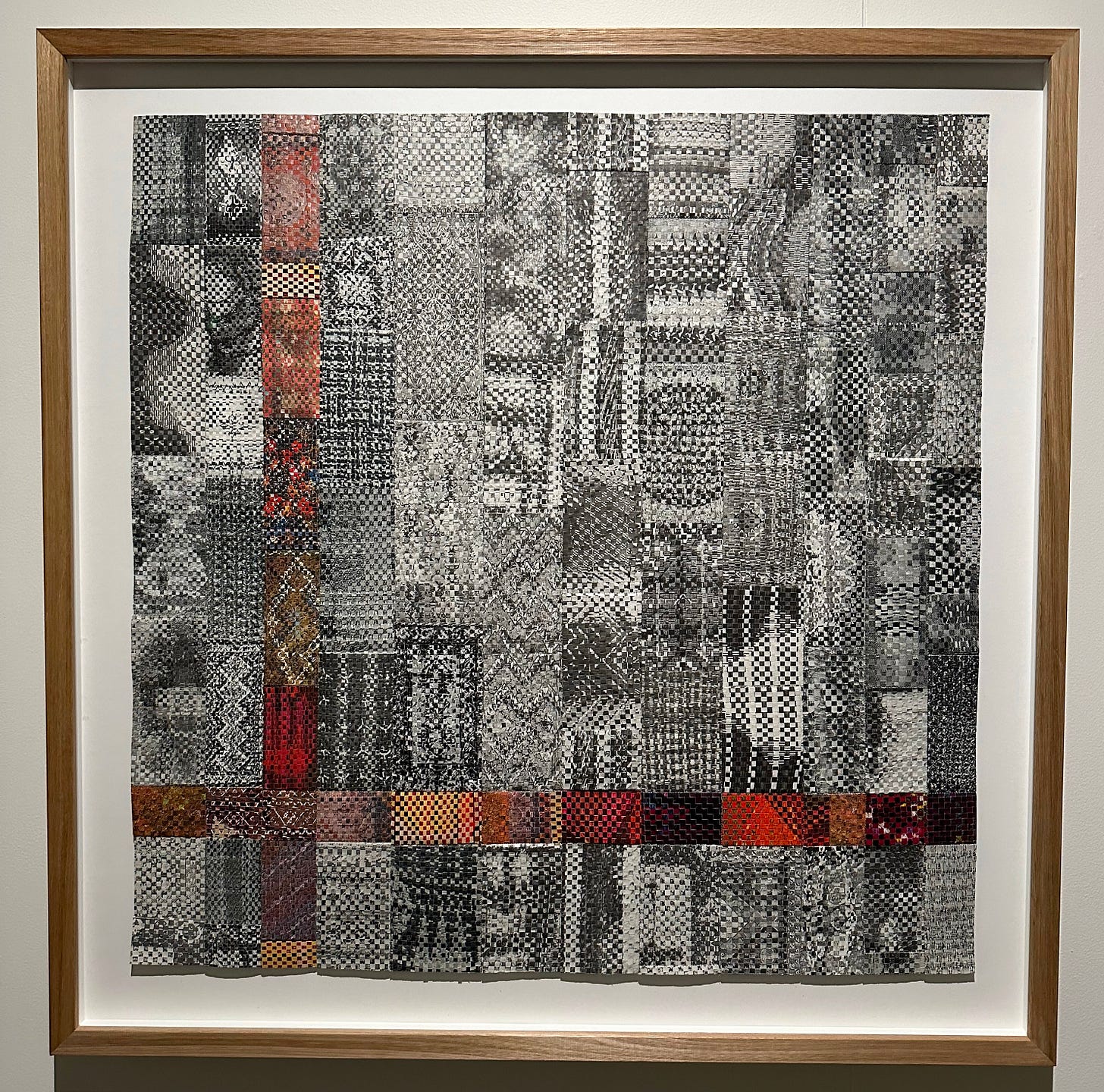

Like Mancktelow’s garment portraits, the Triennial as a whole brings a hidden history to our attention. For other artists it is the history of craft itself – the until recently maligned practices that compose “women’s” work. Blake Griffiths, for example, has woven together images of textiles published during the heyday of craft revival, a work titled Revive, revive! with the intention of ‘critiquing how textile histories, knowledge and traditions have been recorded, documented and passed on.’

The woven strips of technical textile manual look a bit like television static, a type of impenetrable visual language which is unsettling. Woven paper does not have the same softness as other fibers, and once again it is behind glass so my fingers must itch while I imagine what painstaking process was involved to produce the surface.

Griffiths seeks to balance both skills and ideas, creating something unexpected from discarded manuals which exclusively promoted the technical side of a range of crafts. We no longer accept that craft is without conceptual depth or that women’s work can’t be art. This exhibition presents a rich diversity of artists responding to these concerns, always seemingly with one eye on the history of the materials themselves.

Sophie Honess is fascinated with the history of women’s work and draws out the importance of memory and history by gathering her materials from op shops. She writes, ‘I love rummaging in op shops for supplies: fabric remnants, half-completed cross-stitches, left-over yarn, and tubs of crochet hooks and odd buttons. I am prompted to work by these discoveries. They tell the story of their previous owner, producing images of rest: of women in armchairs stitching. The items themselves also speak of rest. They have been resting in boxes, cupboards and drawers, sometimes for decades.’

Oranges, browns and rusty colours with pink highlights, reminiscent of camouflage patterns, produce a highly tactile quality in Rest. Honess has used a vintage latch hook mat and found yarn, leaving some strands looped while others are clipped. The whole is reminiscent of shag-pile carpet. I long to run my fingers across the surface, which is displayed on a wall to remind me that this is art, and not to be touched. Indeed, there are many plaques throughout the exhibition reminding the viewer not to touch the art.

The desire to touch the works is evocative of the tension between art and craft. Craft traditionally did not belong in the gallery because it was a skill applied to a useful and functional item. Devalued when made by the hands of women. The rug was woven and then placed on the floor, the quilt on the bed, the socks on the toes. Art on the other hand was for viewing, on the wall, elevated and indicative of status and taste and a male domain. Such distinctions have been subverted and transformed for many years now and the exhibition breaks them down further.

The exciting thing about textiles, for me, is their relational quality, how we connect to the memory or cultural significance of a garment or the technique that created it, the way they make us feel and their unique ability to transform both space and the body. Take indigo for example, which is used by many cultures around the world. Both Liz Williamson1 and Rachael Wellisch use indigo dye in their work to explore the connections between textiles and the climate emergency. The dye itself is one of those materials that has a hold over people, its alchemical process captivating but performed slightly differently in many regions of the world. It does not dissolve in water, and it does not adhere to fabric unless oxygen is removed first. Until 1800 it was the only way to get a true blue in fabric.

I’ll need an entire newsletter just for indigo.

At the other end of the emotional spectrum is yellow. Kate Just’s Conversation Piece explores the radical potential of a group of women sitting together and making. Using a patchwork of both wool and acrylic yarn, hand knitted and crocheted into varying shades of the artist’s favourite colour: yellow. The large and unwieldy result hangs in the center of the exhibition, to be added to as the exhibition tours. In Mildura this workshop took place yesterday, so I returned to the exhibition for a second time.

A group of all genders but mostly women assembled. The workshop was supposed to follow the artist’s talk, but some of us couldn’t resist and dived into the basket of yarns. In her talk Kate explained how Conversation Piece embodies the contribution of many hands, each contribution representing a unique experience and perspective. We sat in a semi-circle bisected by the Conversation Piece. As Kate spoke about her career—and the ways in which her practice seeks to place craft practices on the same footing as art (even just to shed the ‘craftivism’ tag)—I looked at the undulating yellow patchwork and spotted something unexpected. A tiny little yellow dillybag, very similar to the exquisitely crocheted dilly bags in Bidjara, Ghungalu, Garingbal artist Kate Harding’s work nearby. An easter egg! The artists had connected and it wasn’t just the artworks that were in relation with each other.

I left feeling the warmth of human connections. I learned about knitting circles in my town. About groups of women meeting to create garments for other women impacted by domestic violence. I felt nourished by the feeling I had contributed to the artwork and its message of optimism and collective strength.

The exhibition tours next to Wagga Wagga Art Gallery, with other locations listed here.

Residue + Response is on at Mildura Arts Centre until 13 October 2024.

What an exhilarating exhibition and review. I found the historical connections via the garment portraits fascinating, as you say, 'We must examine the lives of men like Bungaree to unpick the narratives his life has been clad in.' And being a lover of textile art myself, Sophie Honess' 'Rest' to my eyes is a tactile beauty bursting with the joy of a welcoming landscape. That wonderful 'Conversation Piece' by Kate Just, brings to mind the work of bees, connected through their gathering of golden pollen, for the larger task of maintaining the health of the hive. It is so good that an exhibition such as this will travel around the country adding layers of meaning to the imagination of those who will see it.