Artwork 5: My Bed

Looking at personal lives and public selves in the work of Tracey Emin. This edition discusses strong themes originating in the artist's life, take appropriate caution.

Tracey Emin, My Bed, 1998

I’m looking at a dishevelled bed by itself in a gallery space. Surrounded by detritus and carefully placed pieces of rubbish (cigarette packets, boxes, wrappers, tissues, newspaper, and empty vodka bottles, a fluffy white stuffed toy dog, a razor, and a used condom) it is not a neat bed. A little round stool next to the bed holds a glass dish, polaroid photographs and other haphazardly assembled items. The collection of messy objects hugs the edge of the wooden bed frame on a fluffy blue carpet, which also looks like it has seen heavy use. The bed and its white sheets are free of the collected flotsam and jetsam but reveal other signs of life: stockings, underwear a towel and, on the floor nearby, a chained suitcase.

Each item has been placed exactly as the artist herself placed it while residing in the bed for several days. Nothing orbits far from this heady mix but the viewer, I expect can walk around and look into the bed from all sides.

I am looking at Tracey Emin’s My Bed (1998) in a photograph on my browser. I have found several hi-resolution images which show its display in galleries. Part of me is grateful not to see it in person. Am I that put off by the messiness of Emin’s private display? I feel an uneasiness about the visceral nature of the work. It’s so exposed and as a viewer, I too feel overly visible in my looking.

Our public selves, like a social media selves, are the neat and polished personages we want to show the world. Our private selves are messy, unkempt and often higgeldy-piggeldy (to borrow a recent phrase from Madeleine Dore). Emin’s My Bed shows us the raw and personal chaos behind the curtain by placing something so private in public view. It’s private but it is personal? Assembling the bed she shared with intimate partners—smoking, drinking and having sex—in a gallery space brings us the unsansitised bedroom, far from the Instagram-worthy neat linen backdrops we might aspire to.

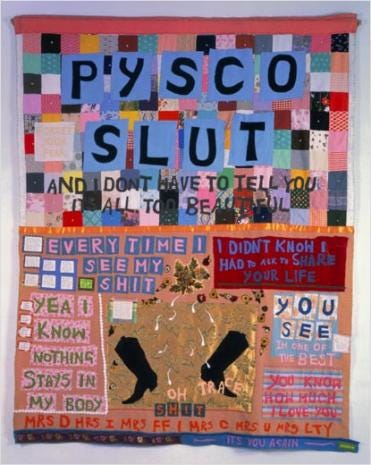

Tracey Emin’s private life has always been central to her art practice, which includes the feminised art of embroidery. In Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963-1995 she embroidered 102 names onto a tent. Audiences giggled as they went in to read the names and came out thinking about everyone they’d ever slept with.1 Emin’s other work looks closely at the intimate details of a life that other people would bury. One reviewer called her life ‘sordid’2 but this has the ring of a critic unprepared to look at what is right before them. More recently, Emin has used social media to further blur the boundaries between art and life.

Emin’s life might be better described as traumatic, rather than sordid. American critic R J Preece lists what he thinks are the elements of a sordid life in his review from 1999. You may well be familiar with the hurdles Emin has overcome in her life, or you can read them listed by Preece like some kind of exotic discovery (do so with a warning). I am curious to see if I can look at (and discuss) her work without resorting to this laundry list.

Emin’s career has always raised questions about what is art and what is life. The private nature of her chosen subject, which is after all the events of her life, are rendered accessible in ways that shocked viewers in the 1990s and 2000s. Her working-class upbringing in Margate, South London, set her at odds with the artworld in many ways. Or as John Molynoux suggested in International Socialism: ‘She makes no attempt to engage in ‘intellectual art speak’ but sticks to unaffected everyday language. This is highly unusual in the art world, the ethos of which is very upper class’. While poverty stricken as a child she still created dolls houses from cardboard, and crafting something meaningful from the materials at hand is also exactly what My Bed does.

A woman’s world

Perhaps it was the openness about her sexual exploits, or the casualness with which she showed her body’s fluids in a hallowed gallery space. Perhaps it was Emin’s behaviour, her demanding presence, which made My Bed a controversial artwork from the get go and earned Emin the title of Brit-celebrity bad girl.

First exhibited in 1998 in Tokyo at the Sagacho Exhibition Hall and then at the Lehmann Maupin Gallery in New York in 1999, where R J Reece wrote the above review of it. This work became Emin’s most well-known when it was exhibited at the Tate Britain the same year and earned her the Turner Prize nomination. A huge amount of media attention followed and her celebrity grew from this profile as one of the Young British Artists, often just referred to as the YBAs. This group, which includes Damien Hirst, Liam Gililck and Sarah Lucas, started exhibiting in the 1980s and were supported and collected by advertising mogul and gallerist Charles Saatchi. My Bed was purchased by Saatchi at the Lehmann Gallery and apparently displayed in his home, in a special room as well as in his gallery. Emin now denies vehemently she was a YBA.3 Instead of conceptualism or minimalism, she nominated expressionism as her major influence.4

Originally inspired by a depressive episode, the artwork included a hand woven noose.

I had a kind of mini nervous breakdown in my very small flat and didn’t get out of bed for four days. And when I did finally get out of bed, I was so thirsty I made my way to the kitchen crawling along the floor. My flat was in a real mess- everything everywhere, dirty washing, filthy cabinets, the bathroom really dirty, everything in a really bad state. I crawled across the floor, pulled myself up on the sink to get some water, and made my way back to my bedroom, and as I did I looked at my bedroom and thought, ‘Oh, my God. What if I’d died and they found me here?’ And then I thought, ‘What if here wasn’t here? What if I took out this bed-with all its detritus, with all the bottles, the shitty sheets, the vomit stains, the used condoms, the dirty underwear, the old newspapers- what if I took all of that out of this bedroom and placed it into a white space? How would it look then?’ And at that moment I saw it, and it looked fucking brilliant. And I thought, this wouldn’t be the worst place for me to die; this is a beautiful place that’s kept me alive. And then I took everything out of my bedroom and made it into an installation. And when I put it into the white space, for some people it became quite shocking. But I just thought it looked like a damsel in distress, like a woman fainting or something, needing to be helped.5

After the Turner Prize dinner Emin made a—now infamous—appearance on a live Channel 4 debate with critics and other high-ranking Royal Gallery folks. She found the discussion boring and walked out, slurring her words but expressing clear enjoyment of the evening. In later interviews she explained she couldn’t remember the night, even after watching the recording with friends. She also didn’t see what the fuss was about. Life’s too short for bad discussions about art.

This event fed the type of media storm artists might only dream about decades later. And audiences lined up.

Because of the amount of press attention, people went to see this dirty bed, as if it was a freak show. But when they got there, they saw something else—the bed, stuff on the walls, whatever. For the Tate, it’s the highest attendance they ever received for the Turner Prize show. There was a massive queue, and when you got into my bit, you couldn’t move.6

It’s not just My Bed that acts as a time capsule, the criticism surrounding Emin and her work anchor this moment in time. And it makes me wonder if, because she is a woman, the shock waves reverberating through the art world, into the media and then onto the street where she was and is often recognised were all the more apparent because of her gender and her class. Traumatised, outspoken and unapologetic woman speaks her mind and turns the events of her life into art with a level of bravado often unseen or unrecognised.

Guardian critic Stuart Jeffries suggested in a recent profile of the artist that ‘Art helps Emin submit the mess of life to artistic order’.7 I like this description of her methods because there is a clear editorial process at play with decisions made about what’s included and what isn’t. There is also something very traditional about an artist exploring the rawness of their existence and the degree of translation that takes place from experience to canvas (whatever form it takes). In this way I think there is so much to learn from Emin’s work.

In 2020 Emin was diagnosed with a large tumour in her bladder which led to the removal of the organ along with her uterus, fallopian tubes, ovaries, lymph nodes, part of her colon, urethra and some of her vagina. Her current work looks unflinchingly at this trauma, as in the past, though she identifies as ‘softer and tougher’, as she told Stuart Jeffries in 2020. A Journey To Death at Carl Freedman Gallery in Margate is her current exhibition, which Jonathan Jones writes warmly about here.

In 2014 My Bed sold for £2,546,500 at Christies. The buyer was Jay Jopling, the art dealer and founder of the White Cube gallery, who—like Emin—made his name in the 90s through the Young British Artists. The artwork is now on long term loan to the Tate, which was Emin’s hope for it. At the time, the Guardian reported that Saatchi sold the artwork as part of ‘clean out’ of his collection and the money was intended to cover entry fees to his gallery and education programs for schools.

Unvarnished truth

Gulsum Baydar describes Emin’s bed as ‘messy, full of “stuff” that is too personal to be offered to the public gaze. Excess is the term that immediately comes to mind.’8 Critic Neal Brown described this as ‘ruthless vulnerability’, which ‘succeeds because of her spirited personal communicativeness and charisma’. Many have tried this and many have failed but Emin's infamous bed has become the iconic example of this approach to art making in the recent era. (Yes I still count the 90s as recent.)

The uneasiness I feel looking at this artwork is in part due to its excess and Emin’s determination not to look away from the painfulness of her life. I’m a bit in awe of these unvarnished truths with which Emin excoriates her self . It’s intimidating and impressive. Her work isn’t about visual beauty, it’s often not beautiful to look at in any simplistic sense—it’s not easy—but there is much to be admired in her process; and beauty certainly isn't everything in art now is it?

Thanks to Clem for suggesting Tracey Emin! This one was a ripper to put together. Please feel free to suggest an artwork or an artist here.

In her interview with R J Preece, Emin describes this scene as the triumph of the artwork.

R J Preece, ‘Tracey Emin’s My bed and other works at Lehmann Maupin, New York (1999)’ Sculpture, 18(10), November 1999, p. 68.

Stuart Jeffries, ‘Interview Tracey Emin on her cancer: 'I will find love. I will have exhibitions. I will enjoy my life. I will', Guardian 9 Nov 2020.

Julian Schnabel Interview with Tracey Emin for Lehmann Maupin, June 2006, p. 2.

Schnabel Interview with Tracey Emin, p. 3.

R J Preece, Exposed: A conversation with Tracey Emin, Sculpture , 21(9), November 2002, pp. 38-43.

Gulsum Baydar, ‘Bedrooms in Excess: Feminist Strategies Used by Tracey Emin and Demiha Berksoy’, Women’s Art Journal, vol. 33, no. 2, 2012, p. 28.