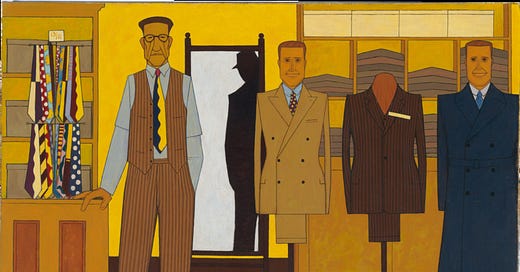

In a men’s clothing store suffused with golden evening light, the proprietor is looking at us. In a mirror behind him the silhouette of a tall man is visible, perhaps he has just walked through the door, browsing after work? The scene has 1950s Mad Men vibes. But we might not notice this first. Two male mannikins with neutral faces and neutral brown hair, standing legless, suited, dominate the right of the painting. At first glance I thought they were real men, transformed into strange horror sci-fi mannikins, guarded by their sinister shop manager. Instead of legs they have wooden stands; instead of arms they have empty jacket sleeves. A headless solid brown pinstripe mannikin stands in the middle. The flatness of Brack’s paint make it difficult to distinguish what is real and what is not, what is alive and what is illusion.

The man in the mirror has been surmised as the artist himself and his reflection forms the only black and white section of the painting.

Looking at the composition as a whole, its glowing mustard background, sharp verticals and horizontals in both the clothing on display and the furniture suggest a harmonious whole. The lighting has a cinematic quality that draws the eye in. You want to look around this men’s wear store. I almost don’t notice the man in the mirror, but soon noticed the tension between him and the proprietor looking at Brack and not us. Was he looking at Brack as Brack painted him? Did he know?

Critics past and present

For Herald art critic Alan McCulloch, writing in 1953, Men’s Wear showed Brack’s ‘understanding of the psychology of “the little man”.’ The world he painted was innocent with its focus on the daily commuter. McCulloch praised the exhibition and noted the artist was able to connect strongly with his diverse but archetypal subjects.

Behind the observation of the merely physical is a poetic intention which saves the work from incidental references, and places it an entirely different category to that of the newspaper cartoon.

These remarks were made of Brack’s first solo exhibition. Held at Peter Bray Gallery Bourke Street in October 1953 it has been credited with launching his career.1

Critic Arnold Shore also praised Men’s Wear:

“Men’s Wear” is a triumph from the completely banal subject matter of a ready-to-wear tailor's &c., he has produced a biting commentary - a canvas which blossoms with a richness of color and design that can fairly be likened to an orchid.

This biting commentary and regard for society’s down trodden also caught the eye of more recent critics. Former human rights commissioner and conservative Tim Wilson, writing for the Institute of Public Affairs, argued ‘no other artist depicts post-war, aspirational, Menzies-era Australia like John Brack.’ Noting also that ‘Brack articulated that hard work, sobriety and aspiration are timeless features of Australian society.’ For Wilson it is Brack’s ability to paint the men and women who would become Menzie’’s “forgotten people” that made him a great painter.

Brack noticed the ordinary in their lives, but Wilson doesn’t see the absolute privilege of their existence and his interpretation celebrates all that this brings.

How should we read this painting in the present?

A man walks into a shop…

Men’s Wear might be the campest painting Brack produced. It might also celebrate quiet Australians and their conformity to suburban routine *cough* dream. Simultaneously, it depicts a kind of urban affluence and privilege, the silhouetted artist figure adding a sinister tone to the warmly lit interior. I think it’s all these things.

There are things about the painting that drew me to it. The warm colours and rigid composition, along with the freshness of it being a Brack painting I hadn’t seen before. And then I stumbled on Wilson’s review of the exhibition from 2009 and I realised how art depicting a segment of the population can be used to further a political agenda. Brack disowned that he painted satire, saying he was an observer:

What I paint most is what interests me most, that is, people; the Human Condition, in particular the effect on appearance of environment and behaviour … A large part of the motive … is the desire to understand, and if possible, to illuminate …

And to question the reality as it was constructible in painting.

There can be no one-to-one translation of anyone’s observations. Brack’s view of the world is also highly interpretable and this is what I like about Men’s Wear. Could the silhouette arriving at a men’s wear shop at the end of the day be stopping by for something other than a new tie? What is the relationship between these two men? Perhaps it’s not sinister at all.

Like I said, it’s a very camp painting.

What do you see?

Men’s Wear (1953) is in the collection of the National Gallery of Australia. The National Gallery of Victoria has a large selection of Brack’s works to view online here.

David Thomas, The Three Players, John Brack (1920 – 1999, Deutscher and Hackett, retrieved 14/2/2022.