On an upper walkway in GoMA’s spacious building Kawita Vatanajayyankur appears on several screens, along the length of the passage. She is clad in a flesh-coloured bodysuit, and performs often mundane, repetitive tasks involving her whole body. Her labour is arduous, ridiculous, and gendered.

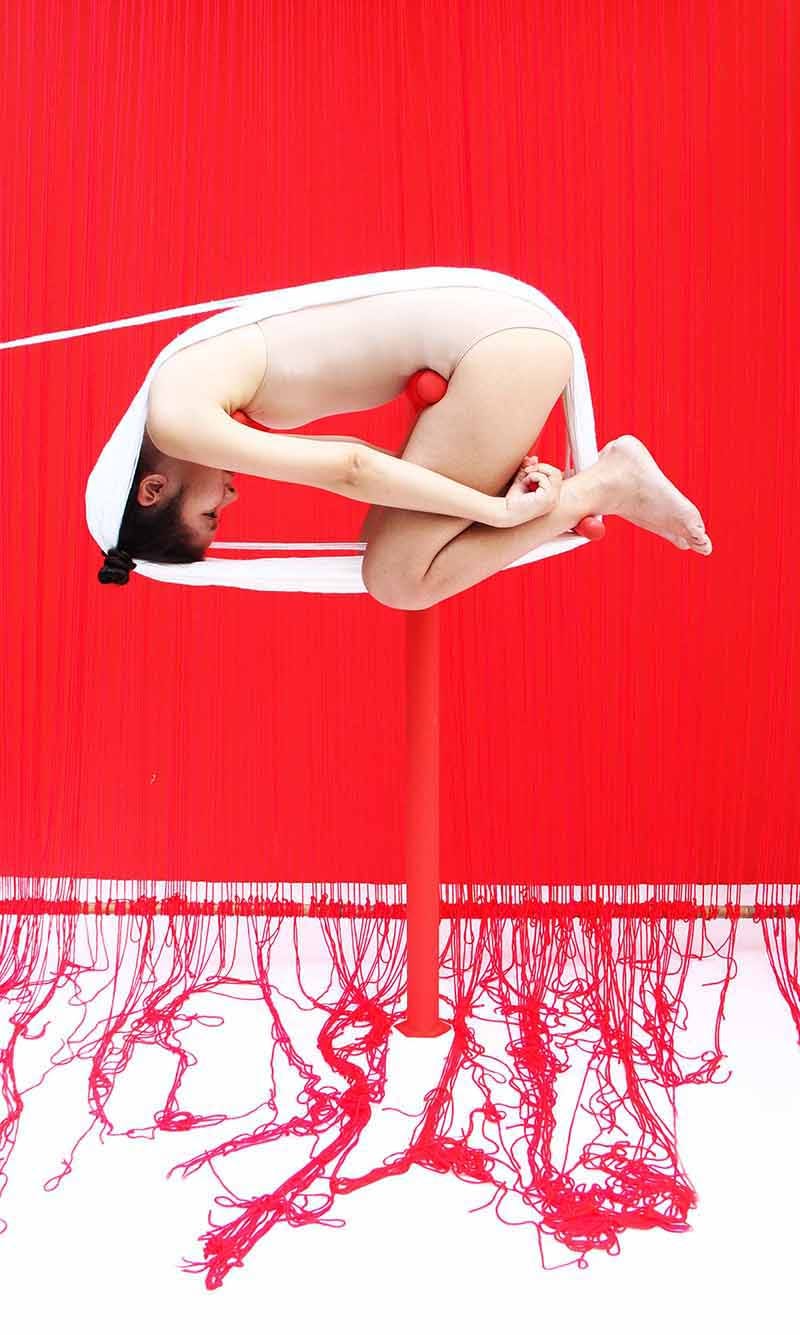

In a series exploring labour exploitation from 2018 titled ‘Performing textiles’ she is the shuttle taking the thread across the loom. Her body much heavier than an actual shuttle flops and falls through the space in a brightly coloured loom. She is then a human knitting machine, seated within a circular frame using all four of her limbs to manipulate a bright red yarn. She is also a spinning wheel, around which a white thread is wound, her body turning over and over in front of a solid red background.

These physically demanding durational works are presented in video form, but they begin life as performances. Vatanajyankur practiced for weeks to turn herself into a scale:

‘In The Scale of Justice, I transformed myself into a working beam scale by turning myself up and down to measure the weight of the vegetables thrown into the baskets that were hanging on my neck and legs. This work was the most difficult by far; it required me to control my strength and power going up and down, while appearing completely emotionless. Endurance became one of the most important aspects of my performance…’

Her 2012-14 series ‘Tools’ was explicitly about female labour. In it her body became the sponge in the washing up, her face sliding up and down a clear glass plate, soap bubbles mixing with stray hair and smooshing her cheeks. The washing up utensils are colourful (eye catching colour is present in all her work), a deep blue patterned tablecloth, a simple white enamel washing up tub and a bright turmeric background draw me in before I realise what the work consists of.

These artworks are positioned in a challenging location within the Asia Pacific Triennial (or APT). On the one hand, viewing an exhibition of this size I always feel pressured to see as much as possible, to quickly find the most exciting and engaging works. These showstoppers are what the APT is known for. On the other hand, how do I give each artist adequate time in an exhibition of this scale?

APT11 features 70 artists and collectives and 500 artworks. As with past APTs this one is spread across the two buildings that make up the Queensland Art Gallery and Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA). The format is established, the scale well-known, and the expectations of viewers and repeat visitors always high. Earlier this year I spent about five hours making my way through the exhibition.

While constantly pulled to take in the next artwork, Vatanajyankur, and video works more generally, challenge the inclination for spectacle and speed. They also remind me, I can only do what my body permits on any given day. I tried to walk past ‘Performing Textiles’, along the walkway to the next possibly scintillating installation. But I couldn’t. Vatanajyankur’s saturated colours and clear reference to textiles stopped me in my tracks. (Readers might know we love textiles here at Slow Looking.) Their location on this thoroughfare, however, felt awkward. As with other video work in APT11 these were not afforded a quiet or dimly lit cinema space.

It might have been deliberate, though. There I stood watching Vatanajyankur’s vulnerable body become a machine, exploring principles of labour and social equity, while other viewers watched me watching her, or walked past. And all I wanted was to sit down.

Five hours is a long time to spend in a gallery. I had begun in the Queensland Art Gallery building, the older, beautifully brutalist beast next to the Queensland Museum. It had taken from me the reserves of focus, saved up for this special day of looking. This seemed appropriate in hindsight as I watched Vatanajyankur’s various labours.

Vatanajyankur’s most recent body of work explores AI and its impact on labour. In a collaboration with Pat Pataranutaporn, from Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Media Lab, The Machine Ghost in the Human Shell (2024) proposes alternative scenarios regarding AI and the future of the human race.

In the APT catalogue Abigail Bernal writes that these performances ‘draw attention to the way a society based on materialism objectifies and dehumanises its citizens, actively confronting the legacies and consequences of late capitalism and the uncertain future of our relationship with the machine’ (p. 205).

Many artists in the APT interrogate the inequality that is their daily reality. In some ways, this has been a defining feature of the APT over the years. A chance for the art-going, educated public to glimpse the global south through their own eyes. It can be a risky business. What if things head too far in the direction of disaster porn? What if making art can’t save your family from rising sea levels or political instability? What if we accept art’s role in documenting climate catastrophe and widening inequality but don’t take action ourselves? Does it just reinforce our own sense of comfort and relief?

For Sri Lankan-born Hema Shironi, the small scale of her embroidered works might deceive the viewer but she is compelled to respond to the life-or-death events of her childhood. Sri Lanka’s civil war (1983-2009) framed her childhood as the family moved continually. Giving careful consideration to the politicisation of language, and the travesties of injustice, is a significant undertaking, which she does through the intimate labour of stitching. In Erasing Flag (2019) five small, fragmented versions of the Sri Lankan flag are hung behind glass. On the left the flag is bright, but fragile looking. Moving to the left, four further iterations show it deteriorating until only a warp and weft thread is left with a hint of the iconic lion and green and orange bars.

In Starving Flag (2022) Shironi has embroidered everyday objects in the shape of the Buddhist flag. This work captured my attention with its detail, but it wasn’t until I read the description that I felt the emotional heft of Shironi’s project. Tarun Nagesh writes in the catalogue that the blue gas bottles—relied on for cooking—are also dangerous and often unavailable. Yellow barriers on the street create new borders and divisions during times of conflict. Red buses are the overused and underfunded public transit system. And white vans, associated with wartime kidnapping are placed alongside orange fuel cans that sparked protests during the recent economic crisis (p. 181).

It's as though by shrinking these objects down, crafting them stitch by stitch, the artist can somehow make comprehensible the enormity of a world torn apart. As Nagesh notes in the catalogue, stitching too offers the possibility that the artist’s world can be mended, no matter how fragile, untethered and decaying the fabric may be.

Throughout the APT I encountered artworks exploring themes on this scale using traditional methods and techniques, dealing with the aftermath and legacies of conflict. This is expected when the Triennial’s remit is a complex geographic region crossing a significant number of nations. Uzbekistan was represented for the first time in this APT. Madina Kasimbaeva’s Palak suzani (2016-21) is an 8-metre needlework using traditional Uzbek methods which the artist has revived since their disappearance during the Soviet era (1917-91). Beautiful and complex, and deeply rooted in women’s traditions, the ‘palak’ (meaning firmament) was traditionally began immediately following the birth of a daughter, and stitched by the mother as a dowry to protect the newlyweds.

Dana Awartani’s Standing by the ruins (2022) also explores cultural heritage and loss. Awartani was raised in Saudi Arabia by her Palestinian parents; her mother’s family have Syrian heritage. She trained in classical Islamic geometry which fuses art, mathematics and spirituality. For this work she has used adobe building practices shared across many ancient cultures including Morocco and Saudi Arabia, and has removed one ingredient, hay, that prevents the bricks from cracking. The resulting design is evocative of ruins as the stars, pentagons and hexagons cover a 4 by 11 metre space with delicate cracks and crumbling sections.

Cultural loss and revival were also present in a moving work commissioned for APT11. Fala Kuta e Toa ko Tavakefai’ana (2024) is a large-scale weaving by Aunofo Havea Funaki and the Lepamahanga Women’s Group from Tonga. This kutu (Eleocharis dulcis) pandanus (lou’akau) work is so large that some of its length remains rolled at the base of the wall it cascades down. It’s possible to view it from two locations – the floor and the mezzanine near the Gallery’s (QAG) entrance. This work is actually a celebration of the vital role women play in sustaining cultural and environmental health through their creative practices. Like so many artworks in the APT, the skill and dedication required to make them and the necessity of preserving the traditions that inform their purpose, really moved me.

As other reviewers have pointed out, the strength of an exhibition like this is its ability ‘to wrest the conversation around contemporary art away from dominant Euro-American perspectives.’ As with previous Triennials, the perspectives of the Asia Pacific region explicitly include the legacies and histories of imperialist incursions and colonial occupations in an age of increasing ecological collapse.

How do we contend with the scale of both the exhibition and the themes it raises? This iteration did not depart from the well-established format of previous years, and while critic John McDonald criticises the emphasis on group and collective artwork production, this (to me) has always been foundational to one important component of the Triennials: celebrating and strengthening communities in the Asia Pacific region. Such endeavours might be fraught and risk cynicism or commercialisation in the contemporary gallery/social space, but are as vital as ever.

The 11th Asia Pacific Triennial finishes on 5 May 2025. There are many works detailed online which I could not detail here. If you visited APT11, what did you think?