Lands and Waters

A dual review of Reimagining Birrarung: Design Concepts for 2070 and the National Wool Museum’s On the Land: Our Story Retold

I am preoccupied with Indigenous representation. I suppose it comes from the research that interests me and the scholars and writers I admire. Everywhere I look I am, like many a progressively minded millennial, seeking evidence that Australia’s blak history is given due respect and recognition.

Two exhibitions in Melbourne and Geelong engage with the place of First Peoples in Australia’s national story in different ways while highlighting the significance of Country. The National Gallery of Victoria’s Reimagining Birrarung: Design Concepts for 2070 and the National Wool Museum’s On the Land: Our Story Retold approach this subject in different ways.

Their subject matter might be very different—the former is about the future of the Birrarung (Yarra) River and Melbourne’s relationship to it told through landscape architecture design, and the latter is about how fibre has shaped the story of Australia told in the context of a wool museum—both have been developed with a sensitivity to the voices of First Nations people, and to varying degrees the voice of Country.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples capitalise Country to give it due significance. Country, as Margo Neale notes in the introduction to Bruce Pascoe and Bill Gammage’s Country: Future Fire, Future Farming, is a ‘worldview that encompasses our relationship to the physical, ancestral and spiritual dimensions, and involves the kind of intimacy evident in the oft-quoted expression ‘The Country is our mother. We belong to the country; it does not belong to us.’’ (Gammage and Pascoe 2021, 5)

Reimagining Birrarung is the first landscape architecture exhibition to appear at the NGV. Though design-heavy, it isn’t what you would expect from a state (capital A) Art Gallery, but it does do conceptual art very well. Imagining what the Birrarung could look like and how humans might interact with her in 50 years’ time requires a few imaginative leaps. In 2017 the first legislation to give living entity status to an Australian river was passed with Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung Elders speaking on the floor of Victorian state Parliament. The Yarra River Protection (Wilip-gin Birrarung murron) Act 2017 is also the first to be co-titled in an Aboriginal language.

Wilip-gin Birrarung murron means ‘keep the Birrarung alive’ in Woi-wurrung language, an imperative which has been given appropriate emphasis in this exhibition while it also seeks to address the pressing questions facing the city as it expands. How can humans better comprehend the river as alive and their relationship to it as vital for both to survive climate change? This was the question I pondered as I viewed the digital imaginings and design concepts of eight design studios.

Humans emerged as the biggest threat, as you could expect. REALMstudios responded to a section of the river from Abbotsford to Clifton Hill and proposed to reverse the expansion of the city using the natural cycles, systems and stories of the river to prioritise co-existence. In their speculative design the connections between people and nature are strengthened by foregrounding the voices of First Nations leaders (something the Birrarung legislation currently aims to do through the establishment of the Birrarung Council).

In spite of these stated aims it is technology that stands out as a key part of the solution in REALMstudios’ design. Their fleet of underwater bots to monitor the river’s health are among the most eye catching in the exhibition, which as a whole requires patience to make sense of the design-heavy displays.

Bush Projects also present a prototype, another welcome physical representation of the future to contrast with computer generated utopias. Their bespoke uniform for a river keeper inspires me to get my hands dirty pulling trash from the Merri Creek (something I should have done more of when I lived there). The garments are a contrasting (and kinda trendy) mix of brown camo, shiny fabric vest and wetsuit material trousers, equally at home on the banks of the Birrarung and the streets of Brunswick. I wonder to myself as I eye of the face covering and gender-neutral sun-protective shirt, whether gear like this will pull us from our apathy and get us all working for Country?

The exhibition is also conceptually underpinned by the advice and advocacy of the Birrarung Council, appointed under the Yarra River Protection (Wilip-gin Birrarung murron) Act to be the voice for the river. (Full disclosure: I’m a former employee). As the voice for the river they are also a rare example of First Nations leadership in the Victorian Public Service fostering exhibitions like this one which are fundamental to imagining a shared future in which both humans and the river can flourish.

Probably the most utopian and visually striking (and therefore controversial) designs are the ones focused on the inner urban section of the Birrarung. Aspect Studios, for example, propose removing a section of the south eastern freeway as well as further increasing the public greenspaces to create an environment for original plant and animal species to flourish while humans share increased biodiversity. Everything is this design, according to Aspect Studios, is realisable with enough community and political will. My experience of the former agrees, but I am sceptical about the latter.

In an emotive animation, Aspect Studios have presented the perspective of the Birrarung herself. This is one of a few subtle indicators of First Nations’ perspectives within this exhibition. Recognising the needs of the river is central in this design, and a first step to considering what type of relationship Melbournians have with the Birrarung. Historically it has not been good and increased community and political will are urgently needed to repair/reverse ongoing damage.

Uncle Dave Wandin, Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung Elder and fire knowledge holder, speaks at the start of the exhibition, probably the most visible component of First Nations’ perspectives in the exhibition. Uncle Dave urges the viewer to learn to care for Country, and follow the protocols of the First Peoples who have said, repeatedly, these are the conditions we must adhere to as visitors on their unceded lands. Have you listened at a Welcome to Country? There’s usually a clear format. We have obligations to leave this place better than we found it, and this applies to non-Indigenous folks, especially the well-resourced ones who have profited from Country.

What a neat segue to discuss the second exhibition.

The convention for exhibition spaces to introduce their subject via a recorded Welcome from Traditional Owners is also used in the National Wool Museum’s On the Land: Our Story Retold. Wadawurrung woman Corinna Eccles welcomes visitors to the space highlighting the interconnections of the Country – saltwater and freshwater Country, mountain Country and inland Country – and reminding us that we must follow Bunjil’s law while on Country.

Wadawurrung people and Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung people are neighbours within the Kulin Nation. Bunjil is the shared creator being for this confederacy of five groups.

I recognise the early parts of the exhibition as an attempt to include Country as more than a resource that is then exploited with the arrival of sheep. Grasslands are introduced, though, through a story of loss. Over 99% of Victoria’s native grasslands have been lost – a common story throughout Australia. The significance of the grasslands will be apparent to anyone who has read Bruce Pascoe’s work: explorers and early settlers encountered idyllic arcadian plains and decided they were awaiting the civilising influence of sheep, before lamenting that it didn’t take long for the sheep (and their hard hooves) to destroy paradise.

But, as the wall text reminds me, the fault can’t be put entirely on the syphilitic shoulders of John Batman and Co. Agricultural practices after World War 2 brought huge impacts, sowing introduced pasture and using superphosphates fertiliser, for example. Today the problem is still us. Urban sprawl is the greatest threat to native grasslands.

So now, feeling a mixture of emotions at this profound loss, the exhibition introduces the next chapter in which sheep arrive on Wadawurrung Country. Geelong was the gateway for these “shock troops of empire” as they headed for the Western District. This is a neat way to introduce the difficult history of wool, to problematise it, but there is also a sense of the pride and nation building in the wall descriptions as well”

“So rich were the Australian grasslands and so well adapted were the sheep to this land that together they created the greatest wool economy the world has ever seen. For over two centuries, sheep farming helped establish the Australian nation”

Maybe that text was just in there for Big Wool.

But the call might be coming from within the house as I stand within the National Wool Museum.

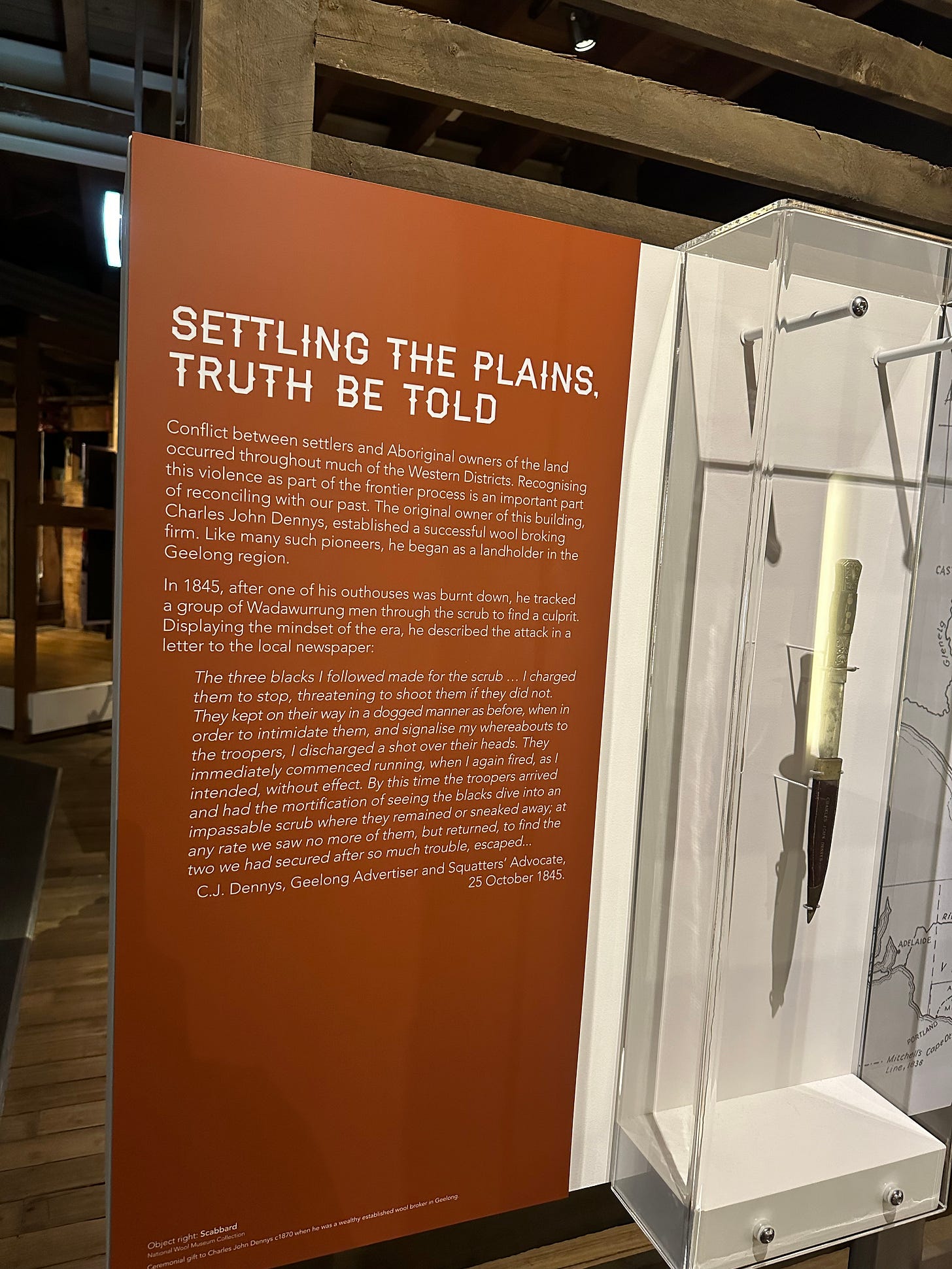

Moving through the exhibition I am struck by the efforts of the exhibition’s creators to unravel the complexity of the wool story. There are strong efforts to balance the monumental loss of biodiversity and Aboriginal culture with the national story that became the dominant national story. Frontier conflict is described and the original owner of the Museum’s building, Charles John Dennys, is quoted describing his firing over the heads of a group of Wadawurrung men. This is a good attempt to un-whitewash the past, but it doesn’t include a Wadawurring voice (this is reserved for the opening of the exhibition as I noted).

As the exhibition progresses chronologically the perspective of the sheep themselves are given some wall space. I chose not to try to understand the machines used for castrating and tail docking, but what didn’t escape my notice was how recently concerns for animal welfare were enacted, despite significant evidence that sheep do in fact suffer when you chop bits off them.

The Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Regulation (2019) came into force on 20 July 2020 with section 8 specifically referring to sheep: pain relief must be administered and sheep’s wool must not be grown excessively. So recent. It might seem like it, but there’s nothing natural about the industry in spite of an overwhelming iconography of ‘Australianness’ associated with sheep. We breed them to grow more wool, just like we breed cows to lactate outside of their normal cycles.

Kinda gross when you think about it and a good example of exhibition unpacking this complex history.

I also walked past a collection of taxidermy sheep, also not my thing, and onto the histories of women and blackfellas as shearers and the battles they fought for equal pay and respect. The voices of Aboriginal shearers are heard here which captivated both me, and the retiree standing in front of the screen for a good fifteen minutes. The Australian Labor movement gets a mention with Queensland shearers striking in the early 1890s to ensure only union members were employed. The displays become more tactile in this part of the exhibition before concluding with a look to the future: solar farms and sheep grazing. Viewers can touch the wool, see where the shearers slept and walk among the various shearing apparatuses demonstrating how the industry has progressed.

Overall, I can see why this exhibition won three awards including a Victorian Community History Award (2021) for Wadawurrung community engagement. It doesn’t shy away from the complexity of the history, but it also still broadly follows the narrative we are familiar with (which is an important part of the brief for a permanent exhibition in a building at the heart of a wool city).

Here’s a sneak peak of the exhibition.

Have you visited the National Wool Museum or Reimagining Birrarung 2070?