Nothing invites a snap judgement like a portrait. More than any other prize the Archibald encourages your average Aussie to say what they think about pictures of people they recognise, love, loath, or maybe have never heard of. This veneer of democracy may not reach beyond the middle class, but this year it does coincide with an Australian federal election encouraging a kind of synchronised popularity contest.

The Archibald received 903 entries and for the first time more of the finalists are women than men. The recently announced winner of the Packing Room Prize—selected by the art handlers who see the works up close and personal—was Abdul Abdulla’s portrait of Jason Phu No mountain high enough. I really like this work! It’s playful, there’s a horse and cartoon birds and strong emotion in the Phu’s eyes.

In the spirit of the democratic season, I’ve chosen 11 works from the 57 finalists in this years exhibition.

Slow Looking has been interested in why we like what we like since its beginning. I understand personal taste as something formed by experience. My love of certain 80s action films did not happen organically. I wasn’t born tapping my feet to swing music (that I know of). And my enjoyment Georgia O’Keefe’s paintings didn’t happen by accident.

If I interrogate what I like too closely I often wonder where my agency was in the process. It’s more interesting, at this moment, to consider taste on a national scale and the unique opportunity to witness well known Australians depicted in new and imaginative ways. How did the judges arrive at this selection of finalists? Will my favourite pick unwittingly also win the $100,000?

Perhaps it’s the proximity to gambling, but this might be as exciting as it gets for many an art-viewing Australian.

The winner will be announced on the 9 May. Here’s my short list.

I’m struck by the eyes of Diana Wood Conroy in this portrait, they suggest long years of intellectual labour and patience. A desire to sit down and gently discuss the significance of her work. Conroy is a textile artist, painter and emeritus professor of visual arts at the University of Wollongong, she is painted here by a first time finalist in the Archibald, Madeleine Kelly who also lives in the ‘Gong.

I enjoy the way in which threads are used here to evoke ideas, as though she’s caught hold of something tangible while working on her next book or article. We should all be so lucky.

A past winner of the Archibald, Namatjira turns the brush on himself. I enjoy how different each representation of his face is, predominantly serious, some seeming older and some younger. The bold, attention grabbing dingo head in the centre seems to echo some of the dog’s own energy, its eyes looking upwards towards (I imagine) Namatjira with wagging tail implied.

A happy yellow power-suit, contrasting shoes and an undisguised openness in the subject’s gaze. The artist has painted her niece and journalist Bridget Brennan combining abstraction and portraiture. She said she wanted to see her niece in one of her paintings. I like the naivete of this picture and the sort of unfocused gaze of the subject makes me think she, too, has blissfully zoned out in the land of delicious yellowness.

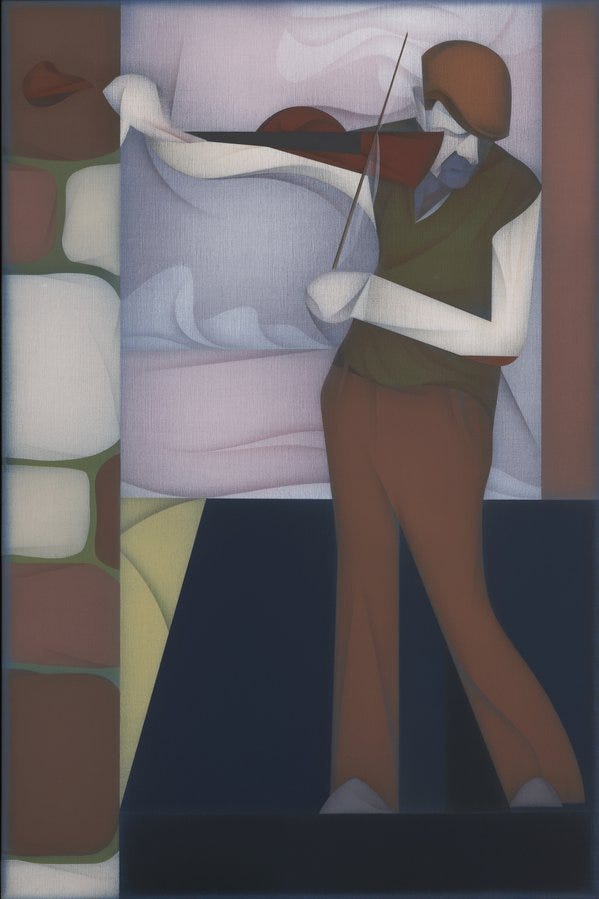

Artists often paint other artists as their chosen subject, and for the Archibald the sitter must be a well-known Australian. I enjoy the sculptural quality of the shapes in this work, particularly the background. They remind me of concrete, which I note is a material also used by the sitter and artist Stephen Ralph. The muted, flat tones remind me of John Brack and the dramatic posture suggests some kind of counter current of masculinity.

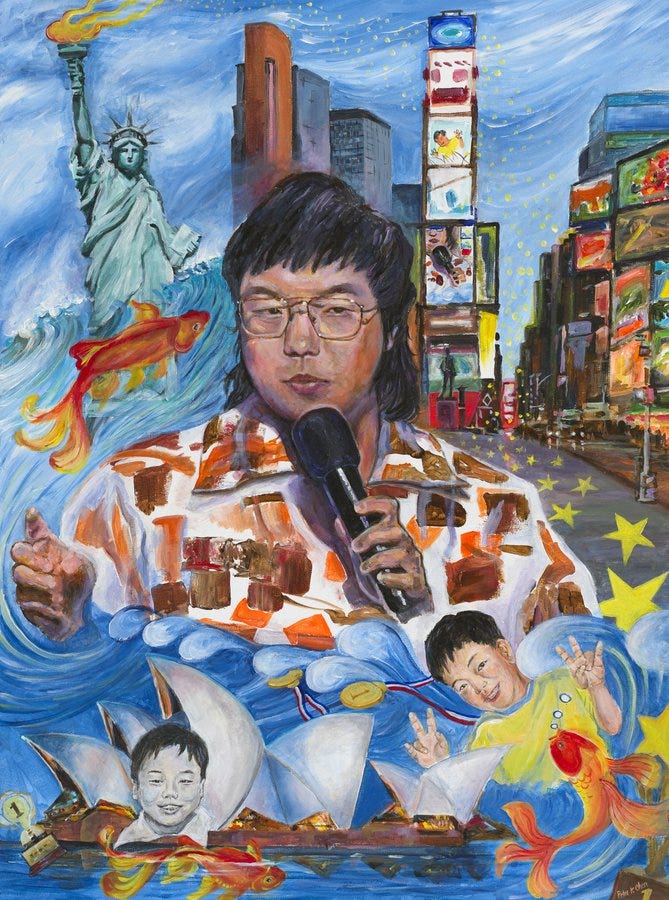

I love that comedian Aaron Chen’s father painted this about his son’s attempt to crack the biggest comedy market on the planet: America. It conjures warm feelings of a parent celebrating their child moving to the other side of the world to pursue their dreams. Strong proud father vibes.

Chen has caught his son’s expression beautifully as a comedian in control of the room, but he’s also scattered evidence of Aaron’s youth and ambition throughout, including references to the Sydney Opera House where he has performed. References to Van Gogh via the rough brush strokes are also no accident.

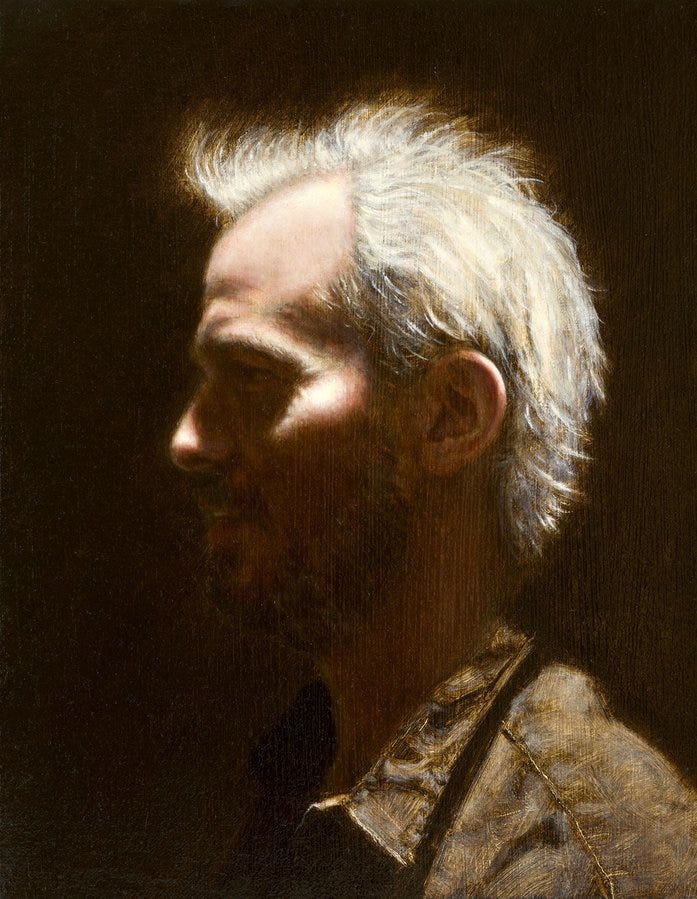

This portrait is a kind of bogan Rembrandt. It’s the product of the artist’s love of Baroque lighting and his friend and artist Keiran Gordon, another Sydneysider. The light falls on the subject’s forehead and receding hairline, it lights up greying hair and the rough fabric of his shirt. The hairstyle and shirt suggest a ruggedness, perhaps he works with his hands or in the outdoors.

This work reminds me that an entire narrative can be built of only a few details about a person. Portraiture invites a kind of close reading, but watch out, fantasies might also spill out.

Created using bisque porcelain and glaze, Sassy Park’s portrait of ceramic artist Casey Chen grabbed my attention because I first thought I was looking at a vase. I didn’t notice the cat until later. I’m drawn to the textual qualities of the surface of this work which come from the materials chosen. It’s delicate and evokes curiosity.

The vase shape suggests the subject is looking out at the viewer through a window, following the gaze of their feline friend. The odd shape of the work reminds me of ancient tiles found in archaeological sites - this one somehow transporting a message of friendship from another time.

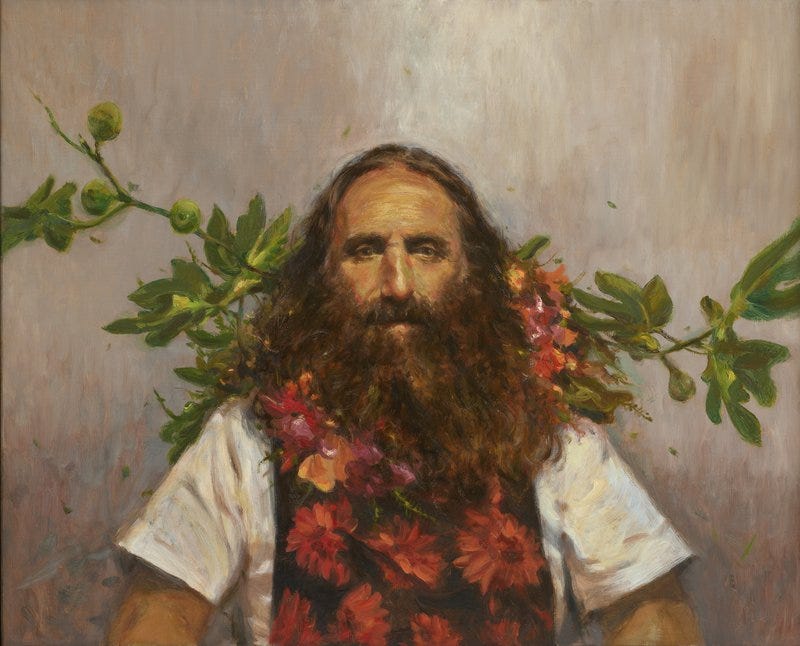

I have a green thumb and Gardening Australia is my favourite thing to watch on TV, so you’d expect me to pick a portrait of Costa. You would be right, but I think this portrait is very different to how we usually see the TV presenter dubbed the green man by artist Evan Shippard. This is a quiet and introspective portrait, the background is muted and formless, and while Costa is accompanied by figs indicating his Greek heritage, there is nothing to tell us what he is thinking.

As a well-known advocate for caring for the environment, and doing everything possible to tread lightly, Costa is a hero of mine. In a reflective work like this, it’s easy to imagine he’s thinking about the weight of responsibility we all have for the enviornment in the times ahead.

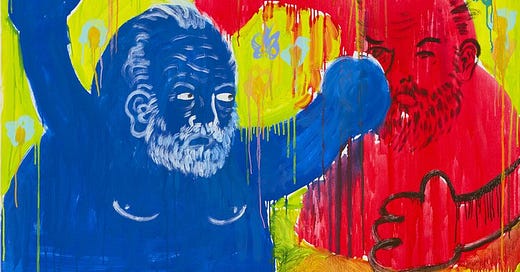

The words ‘hugo’ and ‘fighting’, in reference to actor Hugo Weaving, can only conjure The Matrix and Agent Smith in the mind of someone old enough to have seen it in their formative years or young enough to know a cultural touchstone when they hear of it.

In Jason Phu’s narrative two hugos are fighting in a swamp. Dripping paints and murky golden browns have been pushed across the canvas. There’s an uncertain frenetic energy. One hugo looks at the other with a sort of shocked expression. Why is he letting loose on himself watched by the frogs and insects in the swamp?

My love of the absurdity of this work is only enhanced by the caption supplied by the artist:

older hugo from the future is fighting hugo from right now in a swamp, f*** everyone is a f****** c*** aren’t they, even the older version of you who was sent back in time to stop the world falling to s*** but couldn’t resist finding you and telling you about what you were doing wrong with your life, but like in a really personal and nasty way so that you somehow got into a fight in this swamp and all the frogs and insects and fish and flowers now look on and you both just look like a bunch of f***heads d***f*** horsec*** s***eater worm rat slugs.

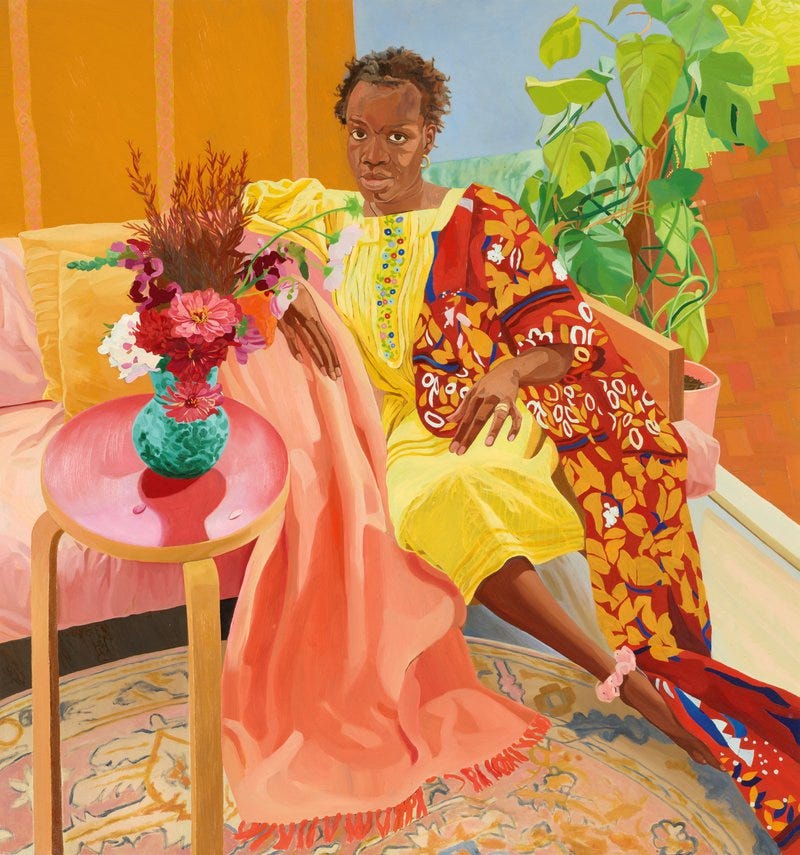

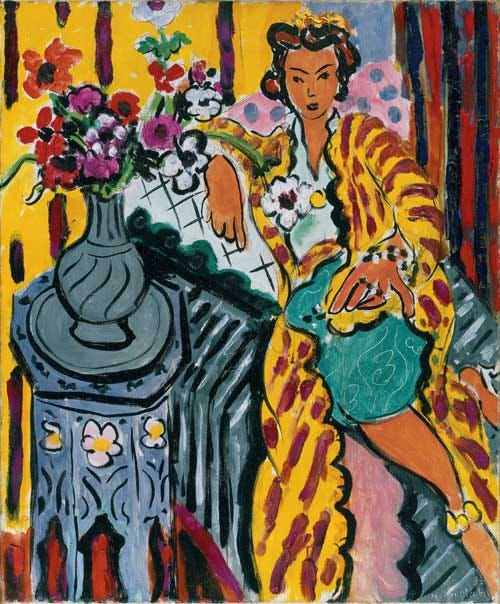

Walsh reimagines paintings from the past in collaboration with well-known Australians, in this work Atong Atem chose Matisse’s Yellow Odalisque. The series is called Hysteria and is about the role of the artist and the sitter, one historically defined by imbalances of power that saw women abused. The artist’s experiences in Paris prompted this work.

I enjoy the vibrancy of colour and texture that working in oil paint on copper can achieve. I enjoy the references to twentieth century painting styles, the tilted perspective and direct gaze of the subject. But it also feels new in the way that makes portrait forever interesting: what can we learn from the person in front of us? What clues have they given?

Atem’s South Sudanese heritage is alluded to through the patterned fabrics surrounding her on a mid-century looking couch. Her pose is relaxed but the higher angle from which we view her makes the space seem like it’s tipping forward. These elements deliberately reference Matisse’s original wherein the subject and space feel even more turned upwards.

This work is arresting to me because of the beautiful way in which Jones captures her own skin and that of her 9-month old son. Here she celebrates his being earth-side for the same time as he was growing in her womb. It is, needless to say, an intimate place to paint from, something special to capture which is now shared publicly. This work is also deceptively simple in the setting which is largely reduced to detailed textures and stripes. Green stripes are repeated on the wall behind, reminding me of the Matisse above. I like the serenity that is created to celebrate this special moment in her and her son’s life.

Each artist’s taste also follows a tradition of choosing subjects that resonate with them for personal, political, or aesthetic reasons. These interconnections are a rewarding part of looking at each work and exploring the relationship between portrait creator and their subject.

Do you have a favourite from this year’s finalists?

All images from the Archibald via the NSW Gallery website. See the Archibald exhibition, Naala Nura Building, Sydeny, with the Wynne and Sulman Prizes from 10 May to 17 August. The exhibition tours after this.